Muttiah Muralitharan bowling for Gloucestershire, 2011Celidh, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Muttiah Muralitharan is celebrated as one of the most formidable spin bowlers in the history of the sport. His journey to an astonishing 800 Test wickets not only set a benchmark for excellence but also immortalized him in the annals of cricket.

Muralitharan’s career, spanning nearly two decades, was marked by his incredible skill, consistency, and an unyielding spirit that saw him rise above challenges both on and off the field.

Muralitharan’s name itself is a story of cultural identity and the global nature of cricket. The variations in spelling—sometimes seen as Muthiah Muralidaran — stem from the transliteration of Tamil into the Latin alphabet. The discrepancies arise due to different approaches in transliterating the Tamil script, which does not always align neatly with English phonetics.

The Beginnings of a Cricket Icon

Muttiah Muralitharan’s journey to becoming a cricketing legend began in the lush landscapes of Kandy, Sri Lanka, where he was born into a family passionate about cricket.

As a young boy, Muralitharan was introduced to cricket by his family, particularly his father, who managed a biscuit-making business and supported his son’s growing interest in the sport. This early exposure played a pivotal role in nurturing his talent, providing him with the initial tools and enthusiasm needed to pursue cricket seriously.

As surprising as it might seem, Muralitharan began as a medium pace bowler, but thanks to the very helpful advice of a school coach, he converted to off-spin at around 14 years of age. At that age, he still played as an all rounder, batting in the middle order.

In 1991, he toured with the Sri Lankan A side to England. While he played five games, he did not take any wickets, but even so, by 1992 he was ready for his debut against the Australians in Colombo in the second test of the series.

Though his debut was modest—with only three wickets in the match—his unique bowling style and potential were evident.

In his early tests, Murali’s figures were solid, but not earth-shattering. It took him 7 tests for him to get his first five wicket hall (5/104 against South Africa, August 1993), and he’d get his second (5/101, also against South Africa) in the next test, but even so, when he arrived in Australia at the end of 1995, he had played 21 tests, taken 78 wickets, and was averaging 30.73.

Solid figures, but not yet earth-shattering. But even so, he was already Sri Lanka’s leading wicket taker.

Unfortunately, it was in the test series that the first controversy of Muralitharan’s career arose, and it would be a controversy that would stay with him, re-appearing at inopportune times, throughout his career.

The No Ball Controversy

In 1995, during a tour of Australia, Muralitharan was called for throwing by umpire Darrell Hair during the second Test at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. Hair deemed his bowling action illegal, calling him for no-balling seven times in three overs. Muralitharan was removed from the attack, but was then returned from the other end, proceeding to bowl 32 more overs without incident.

Just ten days later, in an one day match, umpire Ross Emerson also no-balled Muralitharan seven times in three overs

This incident ignited a firestorm of media coverage and debate within the cricketing world about the legality of Muralitharan’s unique wrist action. His action was cleared by the ICC in 1996, thanks to biomechanical analysis that determined his action was legal, as a congenital defect made it impossible for Muralitharan to straighten his arm and it was only an optical illusion that made it look like he was throwing.

While cleared, Muralitharan was again no-balled for throwing by Umpire Ross Emerson in another one day match in 1998-99 in Adelaide. Muralitharan was again sent for further tests and was again cleared.

Debate still raged throughout the entirety of his career as to whether Muralitharan straightened his arm when delivering the ball. More tests were performed, and then finally, in July 2004, Muttiah Muralitharan was filmed in England bowling with an arm brace to demonstrate the legitimacy of his bowling action.

This film was aired on Channel 4 during a Test match against England. Muralitharan bowled three types of deliveries (off-spinner, top-spinner, and doosra) both with and without the brace, which was designed to prevent any arm bending.

Despite the brace, the deliveries behaved similarly to when he bowled without the brace, showcasing his unique wrist and shoulder action. This experiment aimed to address public scepticism, following a report on his doosra by match referee Chris Broad, and confirmed Muralitharan’s ability to bowl without illegal arm movement.

Breakthroughs and Records and the Race to Most Wickets Ever

Muralitharan’s first 10 wicket haul in a match occurred in his 35th test against Zimbabwe. At the end of this test his average dipped below 30 to 29.40. It had dipped below 30 previously, but this one was significant, because it would never rise above 30 for the remainder of his career.

It was from this time that Muralitharan’s star rose. He became more than just a good spin bowler, but a spin bowler spoken in conjunction with Shane Warne as the best spin bowler in the world.

In his 42nd test, he would take 16 wickets for 220 runs against England, including a second innings tally of 9/65 from 54.2 overs. The only other wicket taken in that second innings was a run out.

Amazingly, while this would be Muralitharan’s best match haul, the 9/65 would not be his best individual innings bowling feat.

Muralitharan would continue to take wickets at a pace never before seen. In his 58th test, he took his 300th wicket, the second quickest to that figure behind Dennis Lillee, who did it in 56.

But after that he was the quickest to 350, 400, 450, 500, 550, 600, 650, 700, as well as the first ever to 750 and 800 wickets.

Between 2004 and 2008, Shane Warne and Muralitharan found themselves in a race to become the highest wicket tacker in cricket. Australia played Sri Lanka in a test series in 2004, and in the first test of the series, Warne took his 500th wicket. Four days later, in the second test, Muralitharan also took his 500th. Both of them were within sight of Courtney Walsh’s record of 519.

It was Muralitharan who overtook Walsh first, taking his 520th wicket in May, 2004 against Zimbabwe. He held the record for a few months, until shoulder injury sidelined him, and Warne passed him. Until Warne retired, he would remain the highest wicket tacker in test.

But, in December 2007, Muralitharan claimed his 709th test wicket – against England – to pass Warne’s mark. He did it in 116 tests, 29 fewer than Warne. Some people, Warne and Walsh included, thought Muralitharan could pass 1000 wickets.

That proved too ambitious, but only because Muralitharan didn’t play enough tests. At the beginning of his 133rd and last test against India in Galle, Muralitharan sat on 792 wickets. Batting first, Sri Lanka scored 8/520 declared, and Muralitharan went through the India side, returning his 67th 5 wicket in an innings bowling performance, with 5/63.

Following on, India weren’t doing much better in the second innings, when Muralitharan bowls a doosra hitting Harbhajan Singh LBW. This was wicket number 799, and India were 7/197.

The cricketing world were waiting with baited breath for that 800th wicket. The Sri Lankan crowd were desperate for it. Every ball came with the expectation that it would be the record wicket.

But wait they had to.

7 overs later, there was a big appeal for a catch off Muralitharan, but it missed the bat. The crowd continued to wait.

In the 82nd over, a wicket fell, the 8th of the innings, but it was Lasitha Malinga who got it. India were 8 down, only 2 possible wickets remaining, and Muralitharan had to get one of them.

Muralitharan kept bowling, occasionally having a break to change ends. At the end of the 92nd over, there was an appeal for stumping, but it was not to be. The wait continued.

India survived to lunch, adding another 40 minute wait to the ordeal.

And then, on the second ball of the 101st over, Muralitharan is bowling again, when a wicket falls.

But it is a run out, not a wicket to Muralitharan. India are 9 down, and Muralitharan has only 1 chance remaining to get the record.

The wait continues.

The 103rd over produces an edge, but there’s no second slip to catch it. The 105th over produces a LBW appeal, but not given out. Muralitharan changes ends, and there’s nearly a bat-pad catch in the 112th over.

But then, finally, after 51 overs of waiting since wicket number 799, the 4th ball of over 116 produces an outside edge to Mahela Jayawardene, and with his last ball in Test Cricket, Muttiah Muralitharan takes his 800th test wicket.

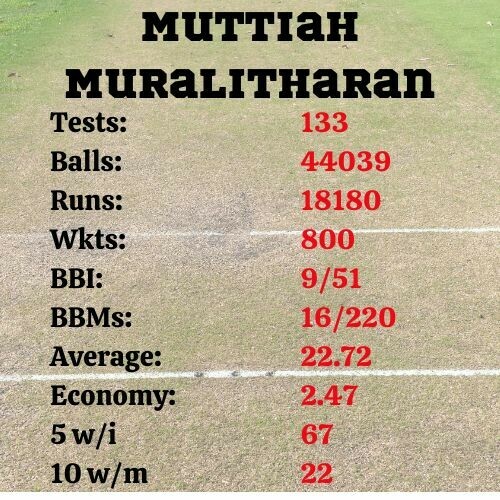

Muttiah Muralitharan’s Test Career … for the stats nerds

There are so many records that have Muralitharan’s name on them.

But first, if you are ever in a pub quiz and someone asks, “True or False: Muttiah Muralitharan took 800 test wickets for Sri Lanka”, be careful. It’s a trick question (assuming, of course, the creator of the ticket actual knows his Sri Lankan cricket). Why? Because Muralitharan didn’t take 800 wickets for Sri Lanka; he played 1 test against Australia for the World XI team, taking 5 wickets and those wickets are credited to his tally of test wickets, but not his tally for Sri Lanka.

So, to be picky, while Muralitharan did indeed take 800 test wickets, only 795 of them were for Sri Lanka.

Still … that’s quite a lot.

But as for records, here are a few:

– He took the most test wickets. (800)

– He took the most one-day international wickets (534).

– If you combine Test, One Days and T20 wickets together, he took more than anyone else. (1347)

– He had the most 5 wicket per innings bowling hauls (67).

– He had the most 10 wicket per match bowling hauls (22).

– He is the only person to have ever taken ten wickets in a match in four consecutive matches, and he did this twice!

– He has also bowled the most test deliveries of any bowler. (44039)

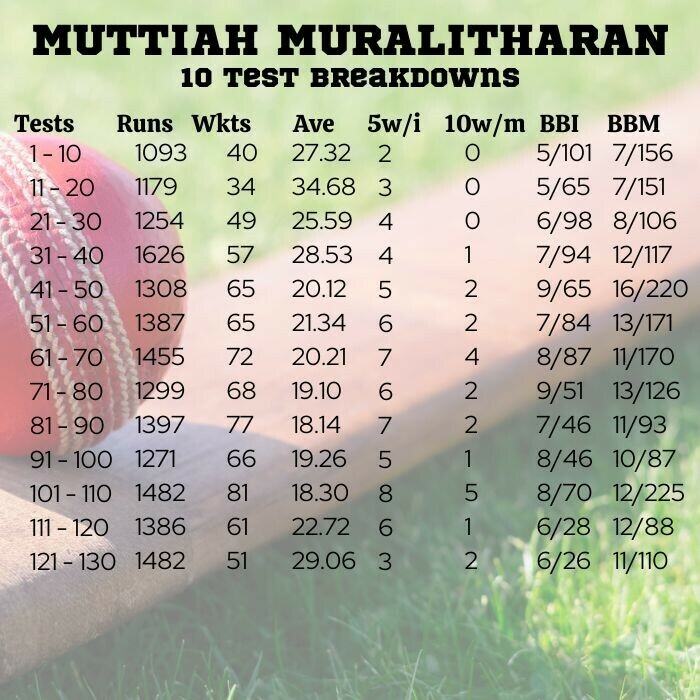

The following aren’t records as such, but they do show the consistent skills of the man.

In 133 tests, which included 230 innings in which he bowled at least one ball, there were only 12 times when he didn’t get a single wicket in an innings.

His best sequence of consecutive matches during which he got at least one wicket in an innings was 52.

His best sequence of consecutive matches during which he got at least three wickets in an innings was 16.

His best sequence of 10 innings, when considering his average only, was a period that culminated in July 2007 with his 113th test. During this period of 10 innings, he took 43 wickets at an average of just 11.6. This wasn’t the most wickets he got in a ten wicket period; that period finished just three tests earlier, when he took 52 wickets in 10 innings. This is particularly stunning because it means he took more wickets during those 10 innings than all of his teammates combined.

On the other side of things, his worst period of 10 innings occurred right at the end of his career. During the ten innings that completed with the finish of his 130th test, he only took 19 wickets, at an average of 49.36.

Two final stats before we leave this section, and these are not about his bowling, but about his batting. When he retired, he had scored the most runs from the number 11 position (623). This has since been bettered by Jimmy Anderson (687) and Trent Boult (644).

And finally, he has scored the most ducks across tests, one days and T20 matches, with 59.

Muttiah Muralitharan: Three Great Bowling Performances

To summarize the performances of a man who had 67 five-wicket hauls in an innings, and 10 ten-wicket hauls in a match into just 3 great performances means you will miss out on many great performances.

If we’ve missed your favourite performance, please mention it in the comments below.

8/46 v West Indies, 2005, Kandy

The two first innings of this match flew by in almost no time. Sri Lanka’s 150 was matched by West Indies 148, to leave Sri Lanka with an unexpected 2 run lead. Muralitharan, the bowler who would eventually bowl the most test deliveries ever, didn’t have to bowl too many in this innings, taking 2/37 of 9.1 overs.

Sri Lanka’s second innings was a lot better than their first, and they declared after scoring 7/375 leaving a very difficult target of 378 to the visiting West Indies team.

But not everything was going the Sri Lankan’s way.

There was the threat of rain, and the great Sri Lankan quick Chaminda Vaas, who had taken 6 wickets in the first innings, was injured.

But this didn’t matter.

Lasitha Malinga got the first wicket, and West Indies were already 1 down when Muralitharan came in to bowl for the first time in the 10th over.

His second over would get his first wicket, an LBW to the doosra, a ball bowled by an off-spinner that spins like a leg-spinner.

A doosra would also give him his second wicket in his 4th over, and again the next ball, both caught by Jayawardene.

At 4/49 West Indies were in big trouble, and Muralitharan already had figures of 3/3.

Rangana Herath took the 5th wicket to fall, Shivnarine Chanderpaul for 24.

After a brief quiet spell, Muralitharan took his 4th wicket in his 13th over, and then another wicket in his 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th overs, his figures going from 3/41 to 8/46 in almost less time than it took to write these few paragraphs about his bowling performance.

After the match, Muralitharan was humble as he often was, saying that while he thought he bowled well, had Vaas not been injured, he (Muralitharan) wouldn’t have taken 8 wickets.

West Indies were all out for 137, and Sri Lanka won by 240 runs.

9/51 v Zimbabwe, 2002, Kandy

This innings would become Muralitharan’s best bowling figures, and as ridiculous as it sounds, it could have been even better.

Zimbabwe started well, and were 0/39 off just 8 overs, when Muralitharan was brought in to the attack, and it didn’t take long for Muralitharan to make a difference. His second ball was caught at first slip by Mahela Jayawardene. He had the other opener out bowled in his 3rd over, and the first ball of his fifth over saw him get a stumping.

Already, after only 4.1 overs, Muralitharan had 3 / 4 (and for those who aren’t Australian, that is 3 wickets for 4 runs.)

A caught behind on the last ball of his 7th over would take him to 4 wickets, and the fifth was brought up at the end of his 12th over, an LBW. Zimbabwe were 5/83 and Muralitharan had 5/21.

A second LBW brought up number 6, he bowled Heath Streak for number 7, and number 8 was also bowled.

Zimbabwe were 8/166, and Muralitharan’s figures were 8/27 off 24, and his home crowd was loving it. Were they about to witness the third time all 10 wickets had fallen to the same bowler?

When Grant Flower fell, also bowled, for a fighting 72 in almost 4 hours, Zimbabwe were 9 down, Muralitharan had figures of 9/47. Not only did Muralitharan have a chance at getting all 10 wickets, he also had a chance at getting the best figures of all time. Jim Laker, the first man to get all 10 wickets, had figures of 10/53.

If Muralitharan got the final wicket for less than 6 runs, the record would be his.

But somehow, Zimbabwe’s number 10, Travis Friend, and number 11, Henry Olonga, kept Muralitharan out as they batted out the final ten overs before bad light stopped play.

Muralitharan would end the day with figures of 9/51, still striving for that tenth wicket, but to add to the drama of the moment, Muralitharan sustained a dislocated finger in the last over of the day, trying to take a tumbling catch on the square leg boundary.

Let’s just repeat that, as that statement shows the kind of cricketer Muralitharan was. He sustained a dislocated finger, trying to take a tumbling catch, that, had he taken it, would have meant he would not have had a shot at taking the best ever test figures.

That just shows the team spirit of the man. There would have been many people, in his situation, who wouldn’t have put the effort in so that they would have the chance to taste the glory for themselves. Not Muralitharan. He injured himself trying to take the catch, putting his team first when even people in his own team, would have preferred he not take the catch.

In any case, the finger was clicked back into place, and Muralitharan, after a night’s rest, would still have the chance to take the record.

On the second morning, Muralitharan, to no one’s surprise, took the first over. The third ball, a simple bat-pad catch, was dropped. The fifth ball, a vicious off-spinner, hit the batsman’s pads, but was given not out by the umpire.

And the next over, Chaminda Vaas, bowling gentle medium pace so that he would not get a wicket … got the wicket, a snick to the wicketkeeper. A couple of the Sri Lankans appealed, mainly out of habit, because they immediately tried to take it back. But because the appeal had been made, the umpire had to give it out, and the innings was over.

It was the second time, Muralitharan had ever taken 9 wickets in an innings, and he was the second person to have ever done that, after Jim Laker, who did it twice in the one game (9/37 and 10/53).

7/155 and 9/65 vs England, 1998, The Oval

For this entry, we get two for the price of one, and what was Muralitharan’s best match bowling figures.

To go through every single wicket would take too long. Instead, we should mention that this test was the only test Sri Lankan played in this ‘series’. For too long, England wouldn’t play multi-tests against Sri Lanka, perhaps not seeing them as good enough to draw a crowd.

It took this game for them to realise just how good Sri Lanka, as a team, was, and just how good Muralitharan as a bowler was, because, from this point on, England would invite Sri Lanka for multi-test series.

Sri Lanka bowled first on what was deemed a good batting wicket. England batter for 158 overs and scored 445 runs, and despite Muralitharan’s 7 wickets – which took him almost 60 overs to get – they felt in a good position. It’s rare to lose games after batting for so long.

Muralitharan would later be a little dismissive about that bowling performance; even though he got 7 wickets, he didn’t think the innings was that successful.

With centuries to Graeme Hick (107) and John Crawley (156 not out) and even some tail wagging from the last man in, Angus Fraser, who scored 32 out of a last wicket partnership of 89, England would have felt the better of the two teams.

That is, until Sanitha Jayasuriya and Aravinda de Silva got together. They took the score from 2/85 to 3/328, with Jayasuriya scoring 213 and de Silva 152.

Even Muralitharan got in amongst the runs, almost equalling his opposite number 11, with a score of 30 runs.

Sri Lanka’s score of 591 meant they had a lead of 146. This gave Sri Lanka something to work with, although it had taken a lot of overs to get to this stage (314).

England clearly didn’t think they could win, and with just over 4 sessions to bat out, they decided to go for the draw.

This suited Muralitharan just fine.

The wicket was still fairly flat. There hadn’t been much deterioration, it wasn’t spin friendly, but Muralitharan just had the knack of finding big turn where others found nothing.

At the beginning of the final day, England were 2/54. These runs had taken 42 overs, and Muralitharan had both wickets.

England continued to fight, runs not being their main objective; just survival.

And Muralitharan just kept bowling and bowling and bowling and taking wickets with balls that seemed to turn square.

All in all, Muralitharan bowled 54 overs in this innings, to go on top of the nearly 60 he bowled in the first innings, and were it not for Alec Stewart being run out, there was a good chance he could have got a ten-for.

Unfortunately, not everyone that saw his bowling appreciated his brilliance. There were still many aspersions on Muralitharan’s actions, including England’s coach at the time, David Lloyd, who was later reprimanded by his board.

Last Word on Muralitharan

Muralitharan was a divisive character, although not because of the man himself, who was renowned for his smile and upbeat nature, even when called a cheat. There will always be people who believe that his action was illegal, despite his action being cleared numerous times. It has, unfortunately, for some people put a small asterisk against his phenomenal record.

So, who was the better spinner? Shane Warne or Muralitharan? Some will point to Muralitharan’s average 22.72, compared to Warne’s 25.41 as proof of Muralitharan’s superiority. Other’s will point to the fact that a far larger percentage of Muralitharan’s wickets were against lower standard teams than Shane Warne, and that Sri Lanka’s pitches were far more spinner-friendly than Australia’s.

I think the best answer is: does it really matter? Muralitharan or Shane Warne? It doesn’t matter, but it can be fun to argue. I think, the cricket world has been blessed to have them both, two very different types of cricketers at the top of their game at the same time.

But in the end, Muralitharan stands alone with 800 wickets, and now with the retirement of Jimmy Anderson and the fact that cricket teams seem to be playing less test matches than previously, we many never see anyone match him.

Do you have any thoughts or memories related to Muralitharan? Leave them in the comment section below.